CRE Back Leverage

The Role of Back Leverage in CRE

Historical / Foundational Context

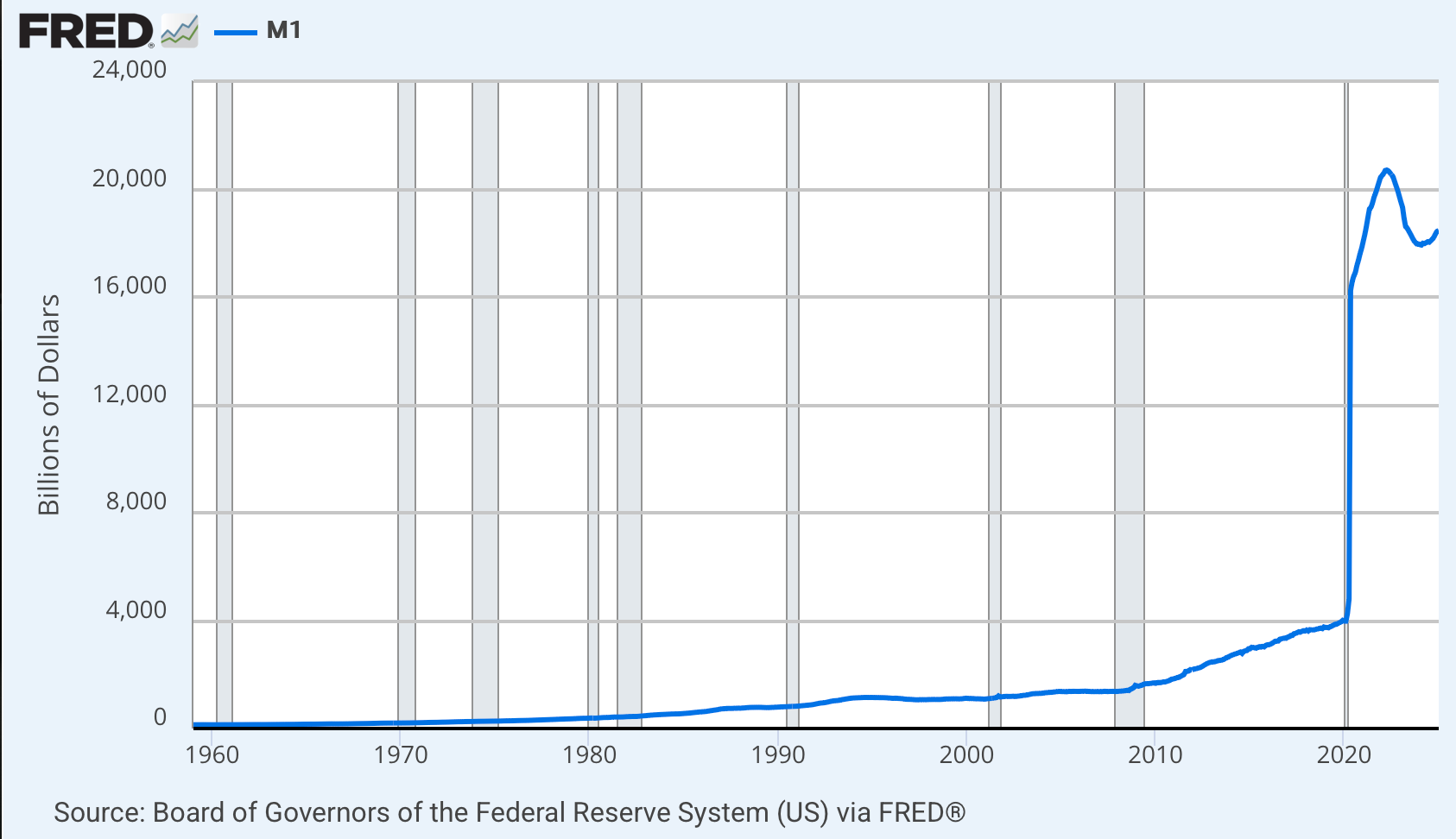

Historically, banks have been one of the largest debt providers in the commercial real estate (CRE) sector. This changed dramatically during the most recent interest rate hiking cycle, where the Federal Reserve raised the Fed Funds rate from 0% to 5.25% in a relatively short time frame. As a result, regional banks across the country experienced significant pressure, particularly from billions in unrealized losses on their books as changes in the risk and reward spectrum challenged asset values. Banks use funds from depositors to issue loans, which they then hold on their balance sheets or sell to the market (other banks / investors). When interest rates are stable or declining, these loans, considered assets, retain or increase in value. However, when interest rates rise, loans made at lower rates lose value, creating substantial risk for banks.

In addition to originating and holding loans, banks also purchase bundles of loans or fixed-income securities from others. The combination of sharp rate increases and leveraging fundamentals contributed to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic in March 2023—marking the third and fourth largest bank failures since 2001. Banks are in the business of borrowing short from depositors and lending long, which creates a potential mismatch between their assets and liabilities when depositors seek withdrawals. With rising interest rates, banks’ balance sheets became impaired by underwater securities, leading to a severe reduction in liquidity—something that the CRE industry relies on to function.

In response, private debt funds emerged to fill the gaps left by regional banks. These funds have grown in number, stepping in to provide capital to the CRE market. However, despite banks originating fewer loans directly to CRE borrowers, they continue to have ways of maintaining market share—chiefly through back leverage.

What is Back Leverage?

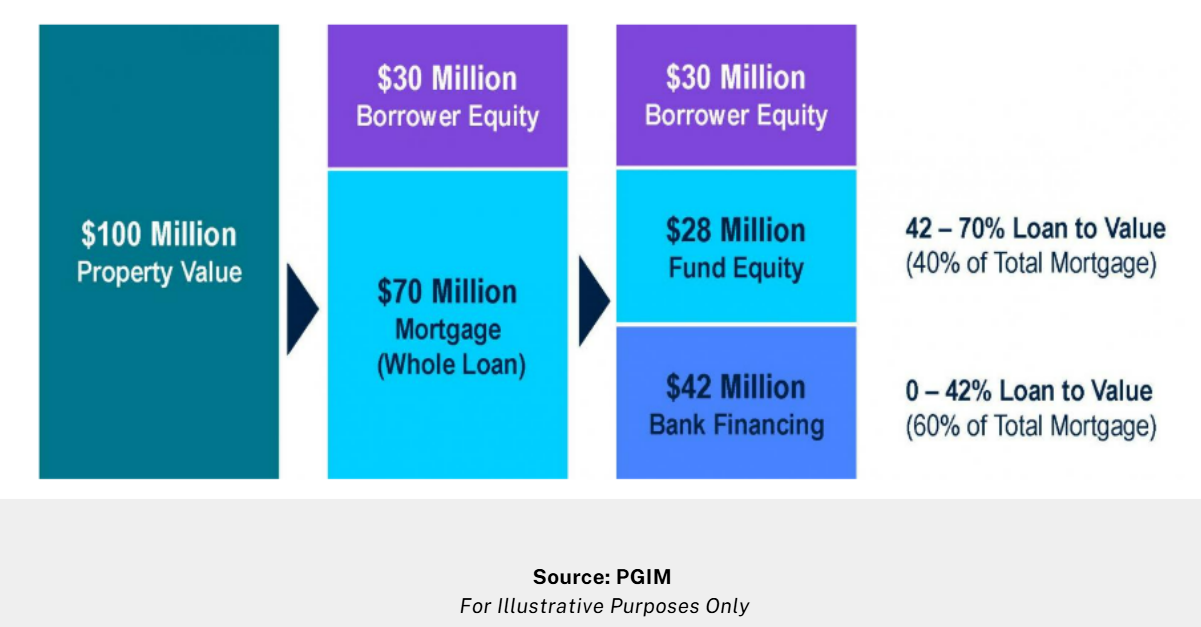

Back leverage refers to financing provided to private debt funds, enabling them to enhance their loan originations, acquire new loans, or leverage existing positions. Private debt funds typically borrow capital from third parties—such as banks—to finance these activities. By using back leverage, funds can improve returns on equity by lowering their cost of capital, thus reducing the equity required to fund new loan originations or acquisitions. This financing model allows banks to gain indirect exposure to the illiquid assets that back the debt fund’s loans.

Back leverage gained popularity when interest rates were near zero because it allowed funds to enhance returns at a very low cost. However, as market conditions soured and interest rates rose, back leverage providers reassessed their exposure to potential losses, leading to a more cautious approach. This hesitation resulted in a reduction in the willingness of back leverage providers to extend additional leverage to debt funds.

Goal of Back Leverage

The goal of back leverage is to create a mutually beneficial relationship between fund sponsors (private debt funds) and third-party funding institutions (banks). For the bank, back leverage provides an opportunity to optimize profitability and balance risk through proper structuring. For the fund sponsor, it enables greater returns on equity while increasing their investment capacity.

Achieving the right back leverage structure requires careful balancing of regulatory and tax considerations alongside the sponsor's goal of securing a more cost-effective and diversified capital base. By optimizing the structure of back leverage, both parties can maximize value while managing their respective risks.

Back Leverage Structures

The primary back leverage structures include loan-on-loan facilities, repo agreements, and private securitizations.

Sometimes these structures can be used for transitional assets that require bridge or construction financing. By utilizing master repurchase agreements, a bank can essentially back a sponsor's business plan, providing capital for new loan originations. Typically, the Sponsor approaches the bank to see if they have an appetite to place a loan on their line or books. The agreements outline several financial covenants to effectively manage risk for the third party.

In some structures, loans or assets are transferred to a special purpose vehicle (SPV). The SPV issues a senior note to the bank lender, while the junior note is held by the fund sponsor. This allows the bank to put up less capital, which increases its lending capacity and reduces risk exposure.

Repurchase agreement structures are often more costly, complex, and reserved for larger funds and financial institutions while loan-on-loan structures are easier and more efficient to execute for small and mid-sized fund managers.

In all back leverage structures, the bank and the fund sponsor work together to balance their risks and rewards. Lenders typically include risk mitigation provisions in the agreements, such as mark-to-market terms, loan-to-value (LTV) thresholds, recourse clauses, and margin call provisions. For example, if the net operating income (NOI) of a property securing a mortgage declines, the lender can issue a margin call to adjust the advance rate provided to the fund sponsor.

Impact of Back Leverage on CRE

Back leverage depends on market stability. Lending is driven by confidence in risk assessment, and for the CRE market to function effectively, there must be consensus on risk pricing. Since credit and mortgage flows play a critical role in determining real estate valuations, any significant shift in liquidity can either stall or accelerate investment activity.

In recent years, back leverage took a backseat due to market volatility. However, it is slowly re-entering the market, albeit with increased safety provisions and more cautious decision-making. As banks regain confidence in market stability, they are more likely to offer back leverage facilities to alternative credit providers, which will, in turn, enhance liquidity and contribute to price discovery for real estate assets. It is safe to say we may see a material increase in types and complexity of structures as lenders aim to capitalize on creating value by filling marketplace and capital stack voids.

Quick Links

Subscribe

Subscribe to receive the latest AEG articles about CRE investing, industry and market insights, and company updates.

invest@alphaequitygroup.com

Investment Disclaimers:

- Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No representation is made that the firm will or is likely to achieve its objectives or that any investor will or is likely to achieve results comparable to those shown or will make any profit at all or will be able to avoid incurring substantial losses.

- In many of the firm’s offerings, investors must be “accredited investors” as defined in regulation d under the securities act. In such cases, investors will be required to submit verification of their accredited investor status through the verify investor platform. The firm will not accept any investments from investors who are unable to submit verification of accredited investor status for relevant offerings. The principles, in their sole discretion, may decline to accept the subscriptions of, and admit, any investor as a member for any or no reason.

© 2024 Alpha Equity Group, LLC